Resource Types

Define the schema of your application's resource hierarchy in the WorkOS Dashboard.

Before your application can manage fine-grained access, you need to define what kinds of objects exist in your product. Resource types are that schema – they describe the categories of entities users interact with and how those entities relate to each other.

Most B2B applications have a natural hierarchy. Users belong to organizations, organizations contain workspaces, workspaces contain projects, and projects contain apps. Resource types let you formalize this structure so FGA can evaluate permissions at any level.

Resource types are configured in the WorkOS Dashboard rather than through code, ensuring your authorization schema is intentionally designed and easy to update as your product evolves.

A resource type represents a category of business entity – something users create, access, and collaborate on. Common examples include workspaces, projects, applications, repositories, and dashboards.

Each resource type has a few properties:

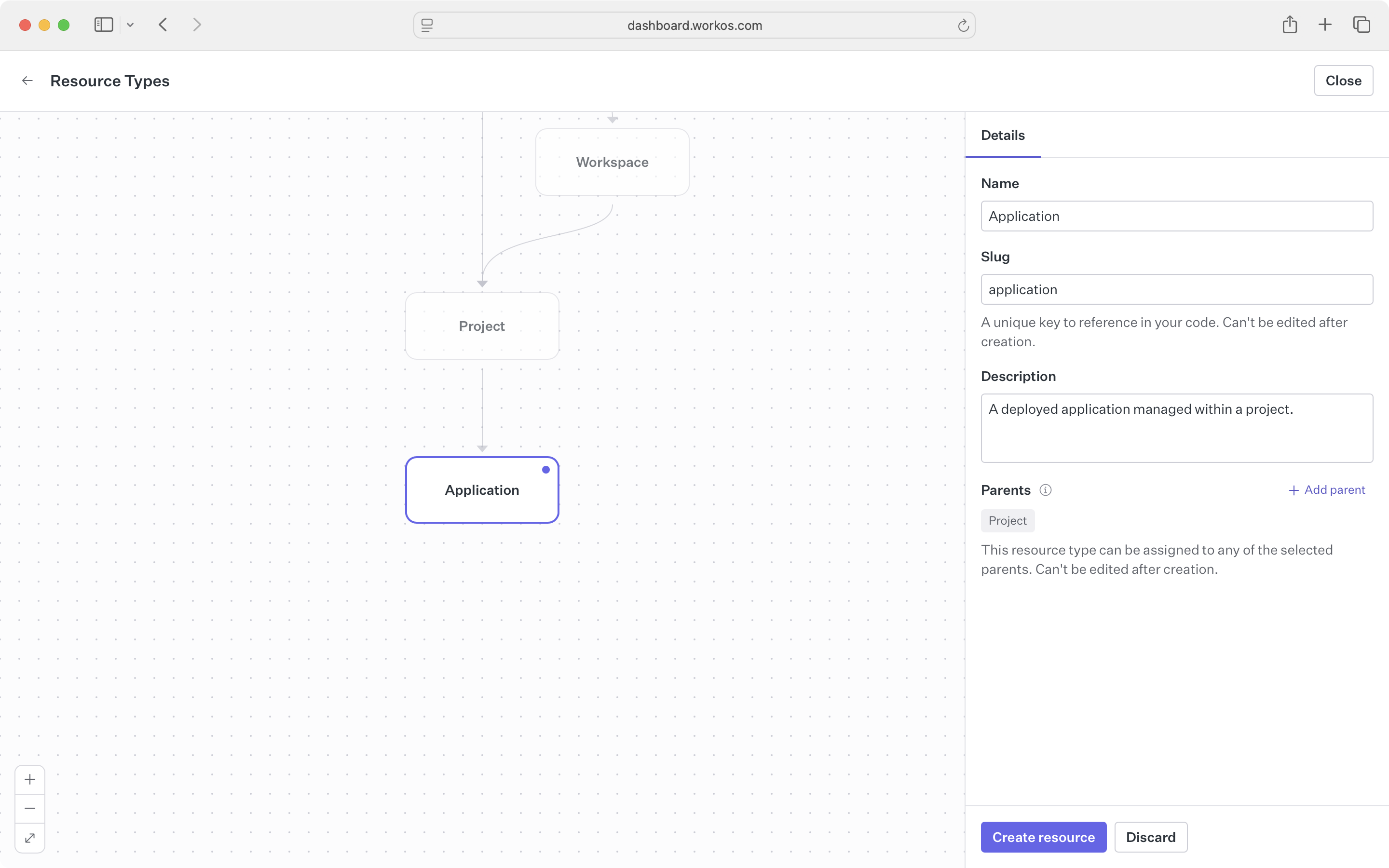

Name is the display name users see in the Dashboard, like “Workspace” or “Project.”

Slug is the URL-safe identifier used in API calls, like workspace or project. Choose slugs that are lowercase, concise, and match your product terminology.

Description is optional text explaining what this type represents in your application.

Parent types define which resource types can be parents in the hierarchy. A project might have workspace as a parent type, while a workspace might have organization as its only parent.

Start by mapping your existing product structure. Think about the entities users create and how they’re nested:

organization (implicit root) └─ workspace └─ project └─ app

Organizations are always the root – every hierarchy starts there. Below that, you define the types that make sense for your product.

When deciding what to model as a resource type, ask whether users can have different access levels to different instances. If all projects in a workspace have the same access, you might not need project as a separate type. If users can be an admin on one project but only a viewer on another, that’s a strong signal to model it.

Keep your hierarchy shallow – aim for 2-4 levels. Deep hierarchies are harder to understand and manage, both for you and your customers.

Multi-tenant SaaS platform: Organizations contain workspaces, workspaces contain projects, and projects contain apps and databases. Customers create workspaces for different teams, with projects organizing their actual work.

organization └─ workspace └─ project ├─ app └─ database

Developer platform: Organizations directly contain repositories, and repositories own branches and secrets. Access is granted at the repository level, with branches and secrets inheriting from their parent repository.

organization └─ repository ├─ branch └─ secret

Analytics application: Organizations contain accounts, and accounts contain multiple dashboards. Each dashboard might have different access levels for different stakeholders.

organization └─ account └─ dashboard

AI agent platform: Organizations contain workspaces, and workspaces contain AI agents, the tools those agents can invoke, and the datasets they access. Users need different levels of access to different agents, and agents themselves need scoped permissions to specific tools and datasets – an agent in one workspace might invoke a search tool and read customer data, while another agent is limited to internal documentation.

What makes this hierarchy distinct is that agents are both resources and subjects. As resources, they live inside workspaces and users control who can configure or launch them. As subjects, agents receive role assignments on tools and datasets just like users do – an agent might have invoker on tool:web-search and reader on dataset:customers. When an agent acts on behalf of a user, it should only receive a subset of that user’s access, never more.

organization └─ workspace ├─ agent ├─ tool └─ dataset

A few constraints help keep your authorization model predictable:

Maximum depth is five levels, which covers even complex enterprise products. Most applications need only two or three.

Single parent means each resource instance has exactly one parent. A project belongs to one workspace, not multiple.

Multiple parent types let a resource type accept different parents. An app might be created directly under a workspace or nested under a project, so both would be valid parent types.

These constraints exist to keep permission evaluation fast and predictable. Single-parent hierarchies ensure that inherited permissions always flow through a clear path – there’s no ambiguity about which parent’s roles apply. The depth limit keeps traversal efficient and prevents authorization models from becoming unwieldy.

That said, the five-level depth limit is a soft limit based on typical enterprise patterns, not a technical limitation. If your use case requires deeper hierarchies, reach out to us to discuss your specific needs.

Resource types are managed exclusively through the WorkOS Dashboard – they cannot be created, modified, or deleted via the public API.

Resource types define your authorization schema, and changes to them can have far-reaching consequences: altering a parent relationship affects how permissions inherit, removing a type orphans all its resources and role assignments, and changing the hierarchy can break application logic that depends on it. By restricting resource type management to the Dashboard, we ensure these changes are made deliberately by someone reviewing the full impact, not accidentally by a script or misconfigured automation.

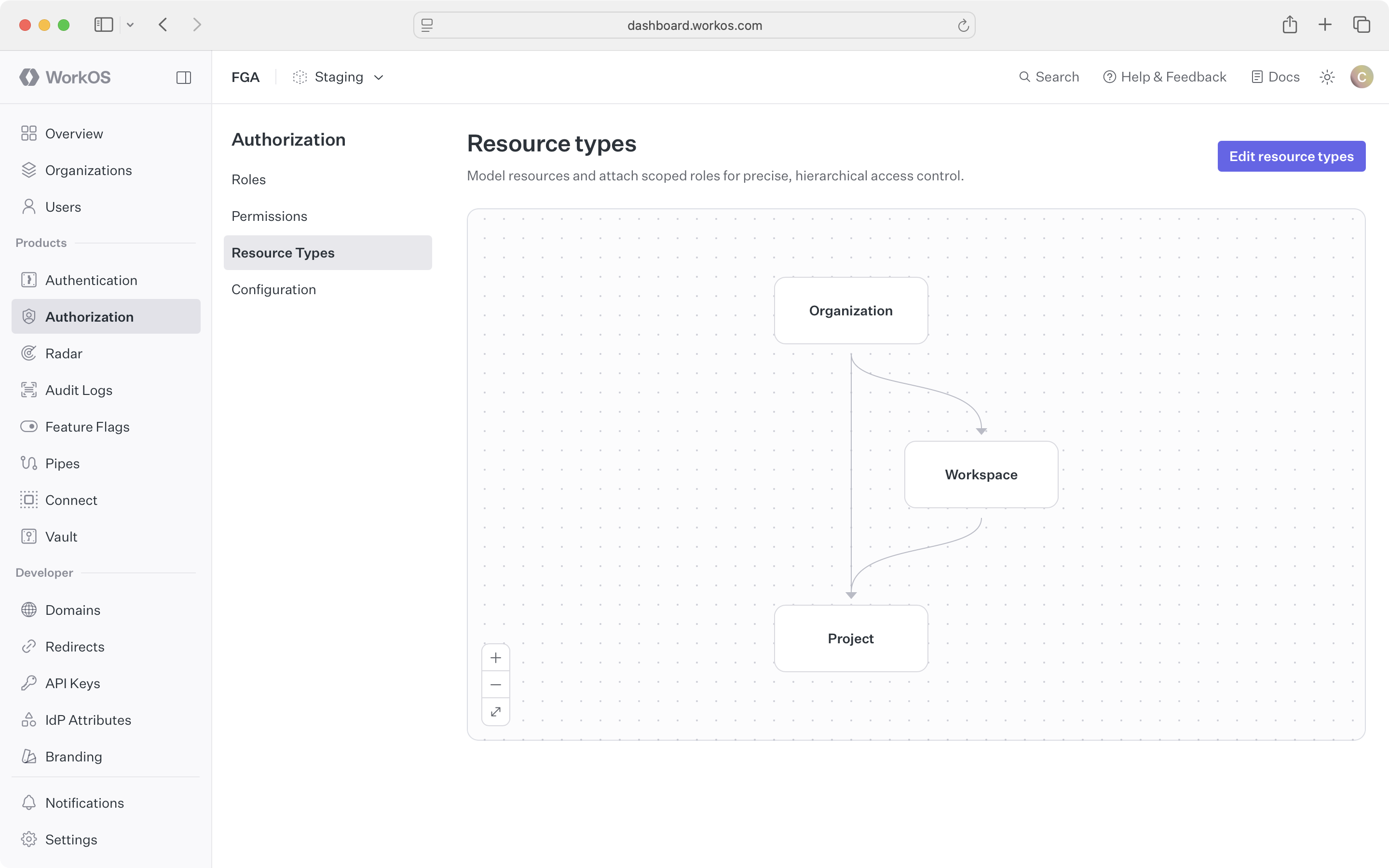

Navigate to Resources Types under Authorization to configure resource types for your environment. The resource type editor provides:

- Visual hierarchy builder to arrange parent-child relationships

- Type configuration for names, slugs, and descriptions

- Relationship validation that ensures hierarchy constraints are met before saving

To create a new resource type, click Edit resource types, provide a name and slug, and configure which types can be parents. The Dashboard shows how the new type fits into your existing hierarchy.

Once a resource type exists, you can update its name and description freely – these are display values that don’t affect API behavior. However, slugs cannot be changed after creation. They’re used in API calls, and changing them would break existing integrations. If you need a different slug, create a new resource type and migrate your resources.

Support for adding parent types is coming soon.

Before removing a resource type:

- Remove any roles and permissions scoped to that type (deleting a role automatically removes its assignments)

- Ensure no child types depend on it – only leaf types can be deleted

Once these dependencies are resolved, deleting the resource type from the Dashboard will automatically clean up all resource instances of that type.

One of the goals of FGA is to make it easy to evolve your authorization model as your product grows. Unlike other systems where changing inheritance rules or adding new entity types requires rewriting complex policies, FGA lets you add new resource types without disrupting existing access patterns.

When you ship a new feature that needs its own access control – say, deployments for your developer platform – you simply add a deployment resource type and define its parent relationship. Existing types, roles, and assignments continue working unchanged.

organization └─ workspace ├─ repository ├─ pipeline └─ deployment (new feature)

You don’t need to predict every future resource type upfront. Start with the types you need today, and add more as you build new features. The hierarchy is designed to grow with your product.