Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) in MCP: What it is, why it exists, and when to still use it

A practical guide to OAuth’s original MCP onboarding method: how DCR works, where it breaks at scale, and why it still matters alongside CIMD.

Model Context Protocol (MCP) makes it easy for clients to discover and talk to servers, but OAuth still starts with an awkward question: who are you? Before an MCP client can request tokens in order to access an MCP server, the authorization server needs a client identity, redirect URIs, and a few safety constraints.

For MCP’s first year, the official answer was Dynamic Client Registration (DCR): a just-in-time way for unknown clients to introduce themselves and get a client_id without any manual setup. The November 25, 2025 MCP spec update added a second answer, Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD), and flipped the default. But DCR didn’t disappear. It’s still in the spec, still supported by major clients, and still the right tool for specific environments.

In this article, we will see what DCR is, why MCP needed it, how it works, where the security traps are, and when you should still reach for it even in a CIMD-first world.

What is Dynamic Client Registration (DCR)?

Classic OAuth assumes a prior relationship between an app and an authorization server:

- A developer pre-registers their app in a dashboard.

- The auth server stores redirect URIs, scopes, keys, name/logo, etc.

- The app gets a

client_id(and maybeclient_secret).

That works fine for the traditional “one app ↔ one API” world, but MCP blows that assumption up. A single MCP client (Claude Desktop, Cursor, VS Code, OpenAI tools, a custom agent, etc.) might connect to thousands of MCP servers, most of which it discovers at runtime, and asking humans to pre-register every client with every server is a non-starter.

Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) is the OAuth extension that solves this bootstrap problem. Standardized in RFC 7591, it lets clients register themselves programmatically, just-in-time: the client POSTs its metadata (redirect URIs, grant types, and related settings) to a registration endpoint (typically /register or /dynamic) and receives a newly minted client_id (and sometimes a secret or registration access token) in response. From that point on, it can run normal OAuth flows exactly like a pre-registered app, while making onboarding self-serve and scalable for an ecosystem the size of MCP.

How DCR works in MCP

In MCP, DCR is the “bootstrap” that happens before the usual Authorization Code + PKCE flow. Think of it as the client introducing itself so the auth server knows where it’s allowed to send the user back.

1) Client fetches MCP Server metadata

When a client connects to an MCP server, it first needs to learn how that server is protected. MCP servers advertise this via OAuth Protected Resource Metadata (a .well-known document).

That metadata tells the client things like:

- “This resource uses OAuth”

- “Here are the authorization servers you should use”

- “Here’s the issuer / audience you’ll be getting tokens for”

- “Here are the scopes this MCP server expects”

Example:

This metadata provides the client with everything it needs to know: the server’s identity, trusted authorization servers, supported bearer methods, and where to find the signing keys.

2) Client fetches Authorization Server metadata

Once the client knows which authorization server to use, it needs to understand how to communicate with it. To do that, the client goes to the authorization server’s metadata endpoint, typically: /.well-known/oauth-authorization-server. This document lists all the information needed to complete the flow: the login URL, token endpoint, supported scopes, grant types, and PKCE methods.

Example:

This is where the auth server publishes its capabilities and key URLs, including:

authorization_endpoint(where users get redirected to log in)token_endpoint(where codes get exchanged for tokens)jwks_uri(so clients/resources can validate tokens)- and crucially:

registration_endpoint

This step matters because the client can’t assume DCR exists, it checks metadata first. If there’s no registration_endpoint, the client knows to fall back to CIMD or another flow.

If a registration_endpoint is present, the client POSTs a JSON body describing itself. This is the equivalent of “creating an OAuth app,” but done via API instead of a dashboard.In MCP, clients usually send:

client_name(human-readable)redirect_uris(where the auth server may send the user back)grant_types(almost alwaysauthorization_code)response_types(almost alwayscode)token_endpoint_auth_method(almost alwaysnonefor PKCE public clients)

Example:

What the client is really saying here is: “Here’s what I am, and here are the only safe places you should ever send auth responses.”

This makes MCP ecosystems truly self-serve: any compatible client can connect to any compatible server, without manual setup or approval steps.

4) Auth server validates + creates a client record

The auth server now decides whether to accept the registration. Typical checks:

- Are the grant/response types allowed?

- Are redirect URIs well-formed, safe, and within policy?

- Is the auth method compatible with MCP (e.g., public client + PKCE)?

- Is the request spammy or rate-limited?

If all checks pass, the server stores a client in its database and returns a response containing at least a client_id:

Some servers may also return:

client_secret(rare in MCP)registration_access_token(lets the client update/delete its registration later)client_id_issued_at/client_secret_expires_at

At this point, the client has become a first-class OAuth app in that auth server’s world.

5) Normal OAuth Authorization Code + PKCE begins

Now that the client is registered, it can start a standard OAuth flow:

- Client sends the user to the

authorization_endpointwith:- the new

client_id - requested scopes

- redirect URI

- PKCE challenge

- the new

- User logs in and consents.

- Auth server redirects back to the approved redirect URI with an authorization code.

- Client exchanges the code at the

token_endpointusing PKCE verification. - Client gets an access token (and maybe a refresh token).

- Client calls MCP tools/resources with that access token. The server must verify that the token is valid and trusted before performing any action.

Why DCR was necessary for early MCP

Early MCP needed a client-registration approach that:

- already existed,

- had clear specs, and

- could work universally across different servers and clients without anyone coordinating ahead of time.

Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) was the obvious fit, and it shipped as the mandatory path in MCP v1 for a few concrete reasons.

- It eliminated human coordination. MCP is a many-to-many ecosystem: clients discover servers at runtime, and servers can’t predict which clients will show up. With DCR, a brand-new client can discover a server’s registration endpoint, register itself, and immediately start OAuth. No admin dashboards, no pre-shared credentials, no “email us to get a client ID.” That plug-and-play onboarding was essential for MCP to feel like a protocol instead of a partnership program.

- It made client intent explicit in a standardized way. DCR requires clients to declare the exact redirect URIs and OAuth settings they plan to use. That gives authorization servers something concrete to validate before tokens are ever issued, especially in a world full of public clients using PKCE. In other words, DCR wasn’t just a convenience layer; it was MCP’s first line of defense for “unknown client shows up, claims an identity, and wants access.”

- It matched “agentic reality.” MCP clients aren’t a small, stable set of long-lived apps. They include IDEs, desktop tools, automation runners, and short-lived agents that can spin up on demand. The OAuth world already had a pattern for onboarding transient clients safely at runtime, and DCR was it. So requiring DCR in early MCP was less about preference and more about aligning the authorization model with how MCP clients actually behave.

That’s why, if you were building remote MCP auth in 2024–2025, you were doing DCR: it was the only standardized way to make “discover → authenticate → use tools” work at ecosystem scale.

The security and operational problems with DCR

DCR works, but once you put it in an MCP-scale ecosystem, a few sharp edges show up fast.

1) Client impersonation

DCR is designed to be open: if a server advertises a registration endpoint, any client that finds it can attempt to register. The server can validate redirect URIs and grant types, but it usually can’t prove who the client actually is.

In MCP, this matters because clients are user-facing. A malicious app can register with a trusted-looking client_name and logo (e.g., “Claude Desktop” or “Cursor”), then trigger a real OAuth login. From a user’s perspective, the consent screen looks legit, but they’re authorizing a spoofed client.

Unless you add extra signals (attestation, allowlists, admin approval paths), DCR by itself doesn’t give you a strong “brand trust” story.

2) Redirect URI games

Redirect URIs are the main safety lever in OAuth: they define where authorization codes and tokens are allowed to go. With DCR, the client supplies these URIs at registration time, and your server decides whether to accept them.In MCP, many clients use:

http://127.0.0.1:<port>/callback(local apps)- custom schemes like

cursor://callback - ephemeral ports

That variety is legit, but it also creates room for mistakes. If your validation is too loose (wildcards, broad localhost rules, arbitrary custom schemes), a malicious client can register a redirect that routes sensitive data somewhere unsafe.

The risk isn’t theoretical: OAuth history is full of “slightly wrong redirect validation → stolen codes → stolen tokens.” MCP just increases the surface area by encouraging dynamic, heterogeneous client environments.

3) Server-side state explosion

Every successful DCR request creates a persistent client record on your authorization server. Even if you store only the basics (ID + redirect URIs), that’s still long-lived state you now own.

At MCP scale, this can snowball:

- Lots of clients are transient or one-off.

- Agents can spin up on demand.

- The same physical client may re-register repeatedly over time.

- You might see registrations from versions, forks, or testing tools.

Suddenly, you’re not just running OAuth, you’re running a client directory service with potentially huge volume, retention questions, and storage/maintenance costs. CIMD emerged largely to remove this requirement.

4) Unclear lifecycle and update rules

RFC 7591 supports updating registrations, but it doesn’t define a universal lifecycle model. In practice, every ecosystem has to invent answers to questions like:

- Should clients re-register every install? Every version? Never?

- What happens if a client changes redirect URIs?

- Do we expire registrations that go unused?

- How do we prevent dead registrations from piling up forever?

MCP makes this worse because clients are diverse and fast-moving. Some will re-register aggressively, others never will, and some won’t implement update endpoints at all. So authorization servers end up with inconsistent, sometimes stale client metadata, and clients don’t know what policy to assume.

That ambiguity becomes an operational burden and a security risk if old redirect URIs or grant settings stay valid longer than intended.

CIMD: MCP’s answer to DCR’s problems

Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD) came from a simple observation: DCR makes the server do too much.

DCR requires every server to accept, validate, and store a new client record whenever a client shows up. That’s workable for small ecosystems, but in an open many-to-many world it creates the exact pressures we just covered: impersonation risk, redirect-URI footguns, state explosion, and fuzzy lifecycle rules.

Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD) flips the responsibility. Instead of asking the server to mint and persist a new client_id, the client uses a stable HTTPS URL as its client identifier. That URL hosts a JSON metadata document describing the client (redirect URIs, name, grant types, etc.). When the client initiates OAuth, the authorization server fetches that document on the fly, validates it, and proceeds, without needing to permanently store a registration by default.

This shift buys MCP a few important wins:

- Less server-side state. Servers don’t accumulate millions of dynamic client records just to support discovery-driven auth.

- Cleaner lifecycle. Updating metadata is as simple as updating the document at the URL; no re-registration protocol or cleanup strategy required.

- Stronger trust signals. If the

client_idis a domain-backed HTTPS URL, servers can use normal web security assumptions (domain control, TLS, reputation) to reduce spoofing. - More web-native scaling. CIMD treats clients like first-class web identities, which fits better with the public, fast-moving MCP client ecosystem.

That’s why the MCP spec added CIMD and made it the preferred path: not because DCR was wrong, but because CIMD is a lower-risk, lower-maintenance default for a protocol that expects clients to appear dynamically and at massive scale. DCR still exists for the environments CIMD can’t cover, but CIMD is now the baseline model MCP wants you to start from.

Cases that still need DCR

Even with CIMD as the default, DCR remains the right choice in several real-world environments.

1) Local / installed clients without a stable HTTPS origin

CIMD only works if a client can host a public, stable HTTPS metadata document. Many MCP clients can’t. Think desktop apps, CLI tools, IDE plugins, or internal agents running on a developer laptop. These often use localhost or custom scheme redirects and don’t have a domain they control for hosting metadata.

DCR fits here because the “identity handshake” happens directly with your auth server at runtime. No public origin needed, just a registration API the client can reach.

2) Enterprise “pre-approval” or policy-gated onboarding

Some organizations want dynamic onboarding, but not open onboarding. They need to apply policy before a client becomes valid: allowlisting by org, restricting scopes, tying registrations to tenancy, or putting new clients into an admin-review queue.

DCR gives you a clean enforcement point: registration time. You can accept, reject, downscope, flag, or delay a client before any user is redirected to consent. CIMD can still be policy-checked, but DCR makes the control plane much more explicit.

3) You need server-minted, server-owned identifiers

CIMD uses a client-chosen URL as the identifier. That’s great for web trust, but some compliance models expect the authorization server to mint and own the client ID, so that client identity is anchored in server state and audit logs.

If your security posture is “clients are valid because we registered them,” DCR matches that worldview better than CIMD.

4) Backwards compatibility and long tail clients

DCR shipped first, and a lot of MCP clients implemented it early. Some of those clients may be slow to migrate, or may never support CIMD. Keeping DCR enabled avoids breaking older tools and lets the ecosystem transition smoothly.

In practice, many servers will run CIMD-first with DCR as a compatibility path for a while.

Best practices for a DCR implementation

If you’re supporting DCR, treat registration like an attack surface. The common best practices include:

- Strict metadata validation. Only accept combinations that make sense for MCP.

- Require

grant_types=["authorization_code"],response_types=["code"], andtoken_endpoint_auth_method="none"for public PKCE clients. - Reject or ignore unknown fields by default so clients can’t smuggle in risky options (like implicit flows) as the spec evolves.

- Require

- Redirect URI allowlists or tight patterns. Redirect URIs are the biggest lever for preventing token leakage.

- Prefer exact-match HTTPS URIs where possible.

- If you allow localhost or custom schemes, constrain them tightly (e.g., specific hostnames, port ranges, or path prefixes).

- Treat wildcard URIs as a red flag and avoid them, unless you’re confident they can’t be abused in your environment.

- Always require PKCE: MCP assumes public clients, so PKCE is the safety net that replaces client secrets. Enforce PKCE end-to-end (challenge on authorize, verifier on token), and reject token requests that don’t include a valid verifier. This also protects users if an auth code is ever intercepted.

- Rate-limit your registration endpoint. DCR endpoints are easy to spam: every call creates work and often persistent state. Add IP- and tenant-based rate limits, and consider lightweight bot/abuse detection. This prevents storage DoS and keeps real clients from being crowded out by noisy traffic.

- Provide admin visibility + revocation controls. Dynamic doesn’t mean invisible. Give admins a way to see which clients registered, what metadata they declared, and which users authorized them. Pair that with a clean revocation story (kill a client, revoke its tokens, and retire stale records) so the system stays manageable over time.

- Use brand trust signals when you can. If you expect certain first-party or well-known clients, add extra verification rather than relying on self-asserted names/logos. Depending on your environment, that could be allowlisted domains, signed metadata, software statements, or device/app attestation. Even simple “known client” checks dramatically reduce impersonation risk.

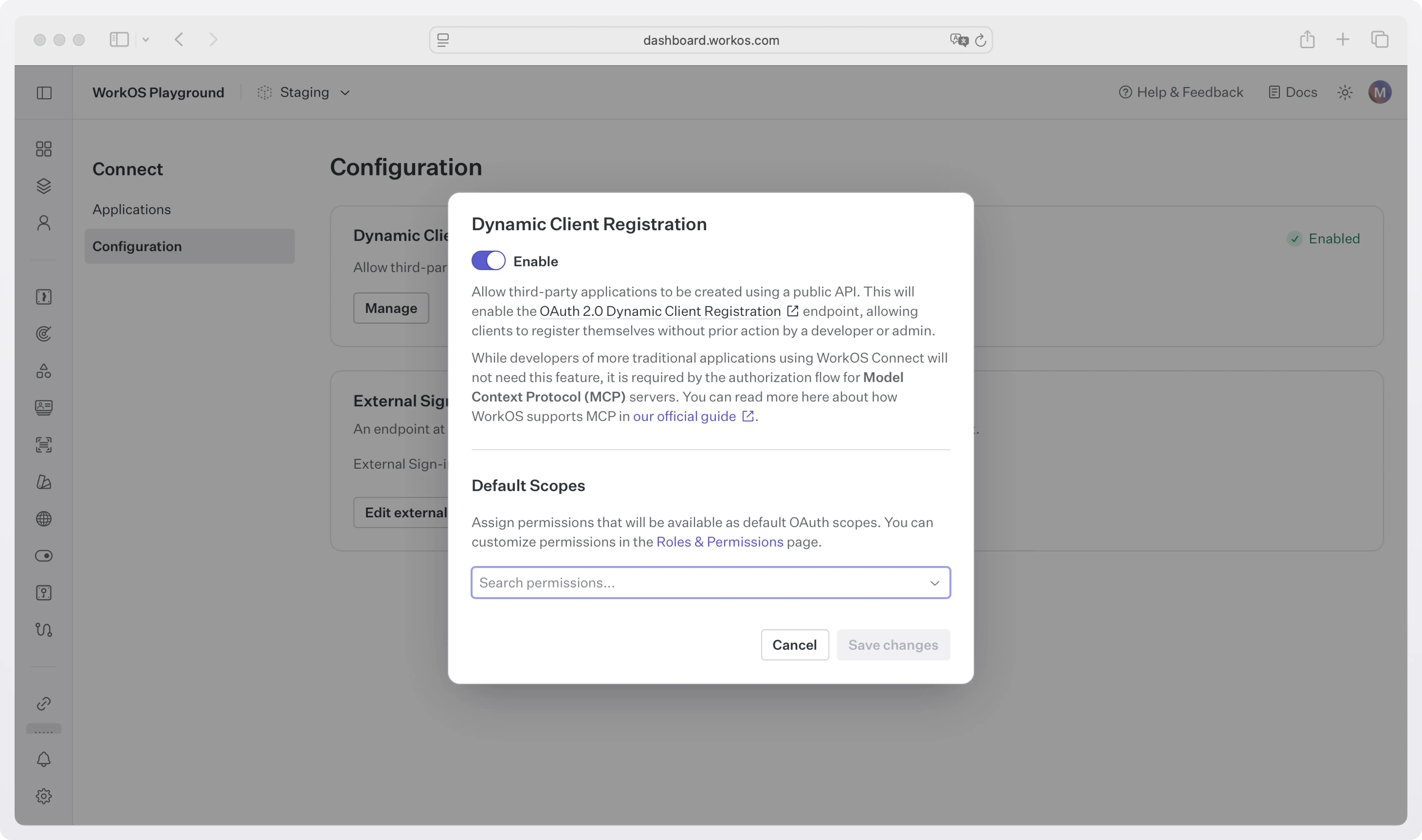

How to enable DCR with WorkOS AuthKit

WorkOS AuthKit supports MCP authorization out of the box, including DCR as required by the MCP spec.

All you have to do is enable it in the WorkOS Dashboard under Connect → Configuration.

In the same dialog box, you can choose the scopes you want to grant clients by default when they register.

That’s it. Once enabled, any compliant MCP client can self-register via your AuthKit DCR endpoint and start the OAuth flow automatically.

Final thoughts

Dynamic Client Registration was MCP’s first workable answer to a real bootstrap problem: clients and servers need to meet and authenticate without prior coordination. It did that well, and it’s still a solid option when you’re dealing with local clients, enterprise policy gates, or a long tail of tools that can’t reliably publish CIMDs.

At the same time, MCP’s growth exposed DCR’s tradeoffs. When every new client creates server-side state and self-asserted metadata, security review and operational maintenance become part of the cost of doing OAuth. CIMD shifts that burden toward a more web-native model, one that scales better and provides stronger default trust signals.

So the takeaway is simple: start CIMD-first, but keep DCR in your toolbox. If your MCP server needs to support public web clients, CIMD is the clean default. If you need dynamic onboarding without a public origin, or you want registration-time control, DCR is still the right move. Supporting both lets you meet the ecosystem where it is today, while staying aligned with where MCP is headed. And if you want DCR and MCP auth to work out of the box without building or maintaining your own authorization server, WorkOS AuthKit provides a spec-compliant, production-ready path with just a couple of toggles.

Read more

- CIMD vs DCR: The new default for MCP Client Registration in 2025: A technical guide to MCP client registration.

- Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD): How OAuth client registration works in MCP

- A developer’s guide to MCP auth

- How to add OAuth to your MCP server

- How MCP servers work: Components, logic, and architecture